Mkhululi Nonjola, Tasmi Quazi & Richard Dobson

Although Asiye eTafuleni’s (AeT) focus is in the realm of urban design and planning with informal workers, contending with legal matters has become unavoidable. This is because informal workers operate from public urban spaces that are often claimed and/or contested, and is consequently an inherently conflictual domain. Furthermore, this is aggravated by an under-developed policy environment, selective interpretation or disregard of bylaws and essential public processes within development projects by urban authorities. In addition, it has been found that there is a lack of knowledge of legal rights and responsibilities by informal workers.

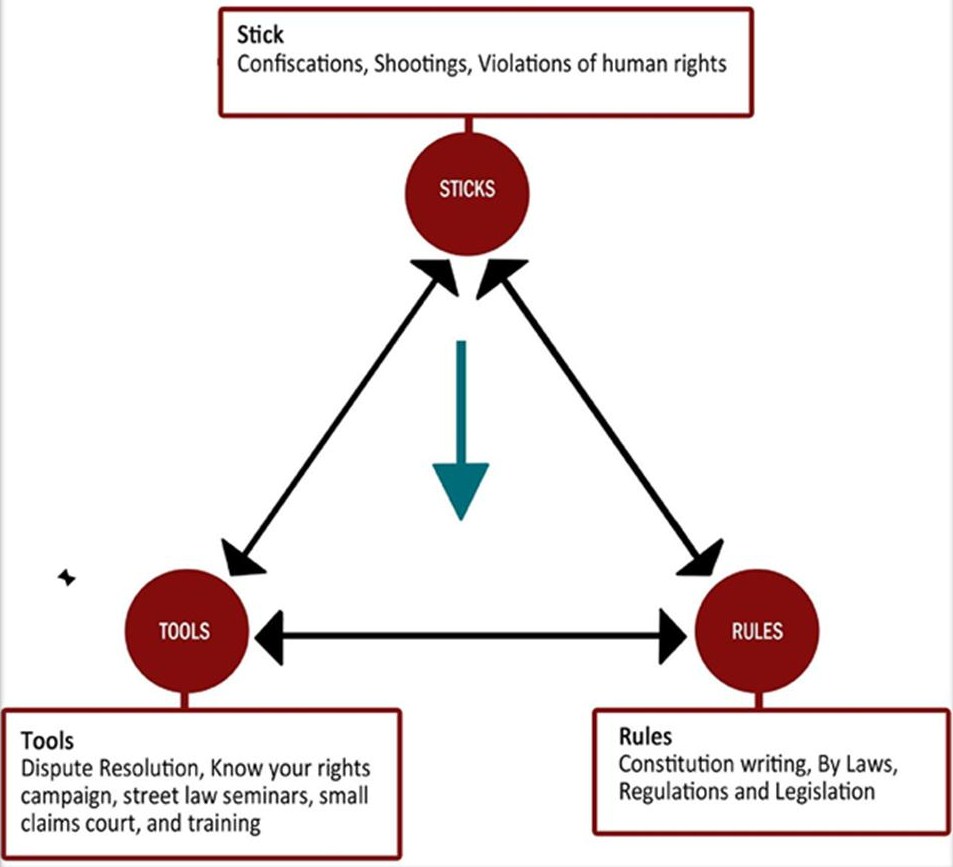

In response to these challenges related to legal matters, AeT conceived a conceptual framework as depicted below.

The “sticks” involve the various disputes and conflicts that informal traders encounter on an on-going basis. These vary from punitive measures by the police in the regulation of informal trade bylaws, unpredictability in the imposition of fines for ‘trading illegally’, and wide discretionary powers that become abused by police officials in the regulation process such as the harassment of traders, violations of human rights and in one case, even the shooting of an informal trader. Furthermore, these include administrative complications such as issuing of trading permits where there is inconsistency in the levying of monthly fees, and burdensome and time consuming procedures at the Business Support Unit. In addition, it involves the non-involvement of informal traders in the formulation of laws and policies making their voices unheard on matters that affect their lives immensely.

The “rules” involves the laws, bylaws, policies, regulations and legislation that constitute the legal environment for informal workers. The “tools” involves a number of strategies implemented by AeT and their strategic partners aimed at minimising the “stick” in order to empower informal workers. For example, disputes resolution mechanisms, application for interdicts, settlement of conflicts, letters to authorities, street law seminars and the Know Your Rights Campaign. These have been implemented with partners such as the Legal Resources Centre, Probono.org, Students for Law and Social Justice (SLSJ), The Office of the Public Protector, Human Rights Commission of South Africa, the KZN Consumer Services and the Commission for Gender Equality.

The conceptual approach is therefore to lengthen the base of the triangle by empowering informal workers through equitable, clear and understandable “rules” and simultaneously negotiating and increasing their legal literacy through effective “tools”, in order to reduce the “stick”. Therefore, the lengths of the triangles represent power imbalances or fault-lines and the ultimate objective is to reduce the amplitude of the triangle through outcomes as reductions of cases of confiscation, harassment and violations faced by informal workers as a result of the “rules” and “tools”.

In elaborating some of the tools, one of the major proactive strategies have included running Street Law Seminars as practical and participatory methods of creating awareness of legal rights, responsibilities and engagement in the democratic processes. This was implemented together with the SLSJ since 2010 with topics such as the FIFA 2010 Street Trading bylaws, Consumer Protection legislation and the regulation of the informal economy, to name some. To read more about these, click on the following links:

Although the law programme primarily involves areas of the policy and legislative environment and mediation, litigation and education strategies; in the field of urban design and planning, AeT advocate that design professionals need to be inquisitive about the legal parameters that they are engaging in beyond their commission, and the potential conflicts therein.

This will contribute to an enhanced and integrated approach that would ultimately benefit informal workers utilising public space. For instance, proactive, positive and sensitive design responses can minimise the “stick” and empower the informal worker. This is best exemplified by AeT’s design of custom-made trolleys and equipment for a pilot project, the Imagine Durban Cardboard Recycling Project. This project has contributed to the stoppage in the confiscation of trolleys and harassment of a group of inner-city informal recyclers by police officials; as experienced frequently prior to the introduction of the project.

In addition, awareness of public processes from a legal point of view is critical because the majority of informal work is done in public spaces with public money. This affects the process of developing a macro programme, such as large development ventures and related processes (e.g. public participation processes in terms of the Municipal Finance Management Act) and the micro programmes in determining appropriate specifications for detailed design of infrastructure for informal workers.

In conclusion, utilising a legal perspective calls upon a well-meaning and comprehensive approach by the city government in the development and regulation of informal work, to give credence to the constitutional promise of a better life for all. This is because of the reality that the policy and practice can easily evolve into exploitative or irregular administration. The range of creative strategies and solutions employed by AeT and its strategic partners are critical for two reasons. Firstly, they address these exploitative or irregular practices. Secondly, they act as a reminder to revert to the original developmental intentions as set out in earlier progressive policies (e.g. Durban Informal Economy Policy) and practices.