Phumelele Mkhize & Tasmi Quazi

The responsibility of designing and producing useful urban infrastructure in the city is assigned to professionals and governing authorities. What would it mean to let the users be shapers of their own spaces and infrastructure? During his internship with Asiye eTafuleni, Mongezi Ncube, investigated the self-built tables of traders (also known as informal workers) in Warwick Junction in Durban (South Africa), in order to better understand the design rationale and mere practicalities of the infrastructure designed, made, and used by informal traders.

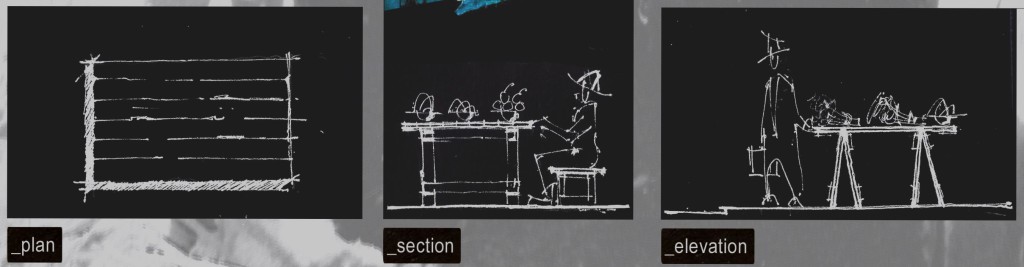

- Sketches of traders’ trestle tables in Warwick Junction made from appropriated wooden warehouse pallets used in the transport industry, by Mongezi Ncube.

Warwick Junction provides ample evidence of the inventiveness and ingenuity of informal traders in providing themselves with simple infrastructure which meets their needs. ‘Sustainability’ becomes more than just ‘smart’ design technologies for environmentally friendly building methods and materials, but the essence of design which enables the end-users which are the traders, to survive and make their livelihoods off the streets. This idea of ‘sustainability’ includes affordability, practicality, and durability as well as locally sourced materials used with minimal waste.

- The local carpenter of Warwick Junction who designs and constructs the trestle tables with minimal waste output. Photo: Phumelele Mkhize.

A common example of self-built infrastructure found in the Warwick Junction precinct, are the trestle tables that are locally made and used by informal traders in the area. Through engaging with traders and documenting the way the trestle tables are used, it was evident that some of the most useful infrastructure are those that are designed simply, yet holistically considerate of their daily setup and pack up routines, as well as storage at the end of a working day.

Furniture as simple as the trestle table enables traders to operate their business flexibly in terms of their use as an extension to the city-provided infrastructure. It also accommodates expansion of their infrastructure needs over time, as their businesses evolve. The trestle table alone still leaves the challenge of needing protection from the elements which is usually addressed by the addition of a tent-like structure made of fabric sewn to a steel frame. The initial modular design of the table is then appropriated over time.

- Sketch showing the challenge of needing additional infrastructure to provide protection from the elements, by Mongezi Ncube.

Perhaps, a lesson that can be learnt by professionals from the way traders use the trestle tables is the process of incremental improvement to urban infrastructure over time as an alternative to radical interventions presented as “finished designs” and especially those without the end-user input. In this particular setting, the end–user input implies understanding the individual and the collective dynamic of informal trading which may include considerations such as size, type and arrangement of workspace infrastructure and what these may imply socially.

- An informal trader in Warwick that has integrated the self-built trestle table with a City-provided trading structure. Photo: Mongezi Ncube.

Although self-built infrastructure meets the initial and immediate needs of traders, the challenges that emerge can be seen as opportunities for collaboration between professionals and the end users. The use of the trestle table as an extension of city-provided infrastructure has already exemplified the realization of this collaboration. To view the research presentations by Mongezi Ncube on the trestle tables of Warwick Junction, click on the links: poster 1 and poster 2.

Great article