Tasmi Quazi

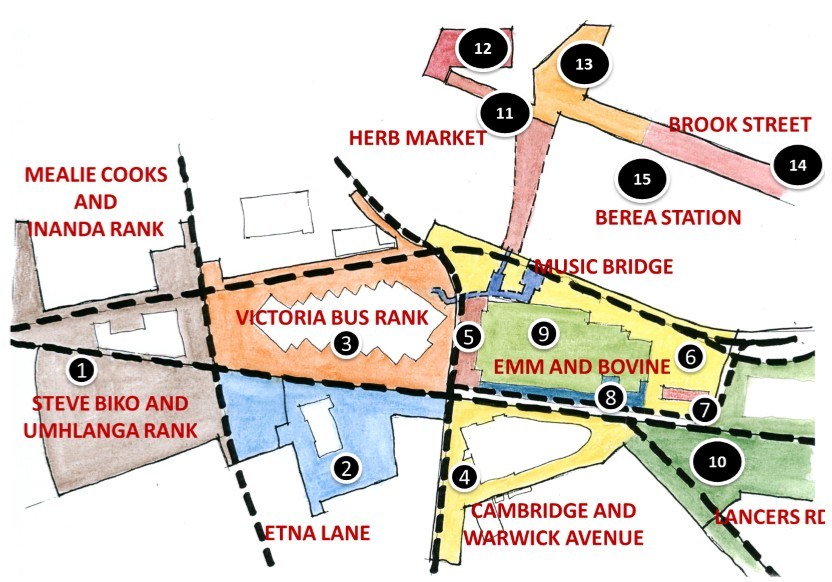

Kanyenathi, the Comic-Relief funded project of three years to be implemented across three informal economy districts in Durban, kicked off in October 2014 with a series of community meetings. From January till July 2015, a major project activity – which was the training for and implementation of the infrastructure audit – was completed. Whilst the previous article reported on informal worker perspectives of the infrastructure audit, this one will reflect on the organisational perspectives of the process and implementation of the audit as it hit the streets.

- AeT staff members in the foreground with a CBD trader leader during the pilot phase of the Infrastructure Audit. Photo: Rhonda Douglas.

Project focus unifying fragmented leadership

A universal challenge of working with informal workers is that their community structures are assumed on a voluntary basis unlike the union movement. Their participation is therefore subject to disruptive external conditions such as xenophobic attacks, harassment, and taxi violence. In addition, some of the informal workers have higher degrees of agency than others based on political opportunism and alignment with particular power dynamics.

- The Infrastructure Audit team mostly dominated by trained informal workers with support from the AeT staff and university student assistants. Photo: Chantal Froneman.

In general, the inclination of their participation is towards any opportunity that would advance their position within the precarious environment of informality. This complex reality provides a divisive leadership environment whereas the Kanyenathi project focus for appropriate infrastructure and services is suggesting a shared and universal concern, which has the prospect of unifying the informal worker leadership.

Peer-learning through cross-pollination

Through the active participation of informal workers as trained fieldworkers, and through shared meetings and focus groups, informal workers are showing greater levels of awareness of the various challenges and opportunities impacting their colleagues within and outside of their informal economy districts. To curb research bias, AeT emphasised ethical interviewing techniques during the training and through simulations; assigned trader fieldworkers to informal economy districts other than their own; and asked the student assistants to conduct independent surveys in every district.

- Independent student survey in foreground. AeT staff member assisting with logistical coordination in background. Photo: Chantal Froneman.

The deliberate ‘cross-pollination’ of participation resulted in new and shared learning amongst informal workers from different districts, who had previously not interacted. Furthermore, the participatory approach has served to build stronger relationships with AeT and participating informal workers, and better inter-relationships between the leadership of various nodes through attendance of common meetings, focus groups and the cross-district fieldwork.

Diverse and broad-based participation

The recruitment of informal worker participants proved to be successful at 2 levels: the recruiting and nomination process included all existing leadership, and was carried out in a democratic fashion. Innovative methods were conceived and implemented to map and zone the survey areas, and to match those zones to relevant leadership structures. The project originally targeted the participation of 15 informal worker leaders, however the overall participation level grew to 49 in total which reflects that there has been heightened interest in the project, and the leadership was able to canvass the buy-in of other informal workers to attend subsequent Project meetings.

- A feedback session after fieldwork. In front, is a young trader from Warwick Junction, and behind him are AeT staff members and a student assistant to the far right. Photo: Richard Dobson.

In addition, the project activities such as the audit required the recruitment and training of additional informal workers with particular skills and aptitudes who were not previously associated with the leadership. Three sets of training sessions were conducted to draw on different skills from the informal worker community: 1) questionnaire training; 2) spatial survey training; and 3) community representation training. User-friendly and innovative survey instruments were designed to make the fieldwork administration more accessible to the informal workers; e.g. the comprehension of tape measures, forms translated to Zulu, visual aids for the conceptual understanding of spatial mapping and the use of digital cameras.

Project branding

The branding of the project, which builds on the street culture of political events being branded through regalia, has become an important advocacy tool which was unplanned. The “Kanyenathi” brand (which means “with us” in Zulu) and its associated imagery (depicting the storyline of the project in symbolic form) has become easily identifiable through community representative meetings and the infrastructure audit fieldwork. These are prevalent visible reminders that the project is underway. Effectively, the informal workers have become the ‘billboards’ of the project.

- The technical team hard at work measuring and photographing surveyed informal workers in the bustling CBD. Photo: Chantal Froneman.

The comprehensiveness of the infrastructure audit with a participatory approach has resulted in not only enormous amount of useful data but also required greater levels of coordination effort. AeT has been encouraged by the level of competency and aptitude of the informal workers in their roles as researchers and community representatives suggesting that the participatory method has long-term relevance and application. It also proved to be a new and powerful tool for informal workers to engage with their colleagues on the universal challenge of infrastructure, basic services and urban management needs. Lastly, though AeT has provided support to external research projects in the past, this project has allowed the organisation to move into a leading role in new and innovative research.