The challenge: informal worker mothers

Roanne Moodley

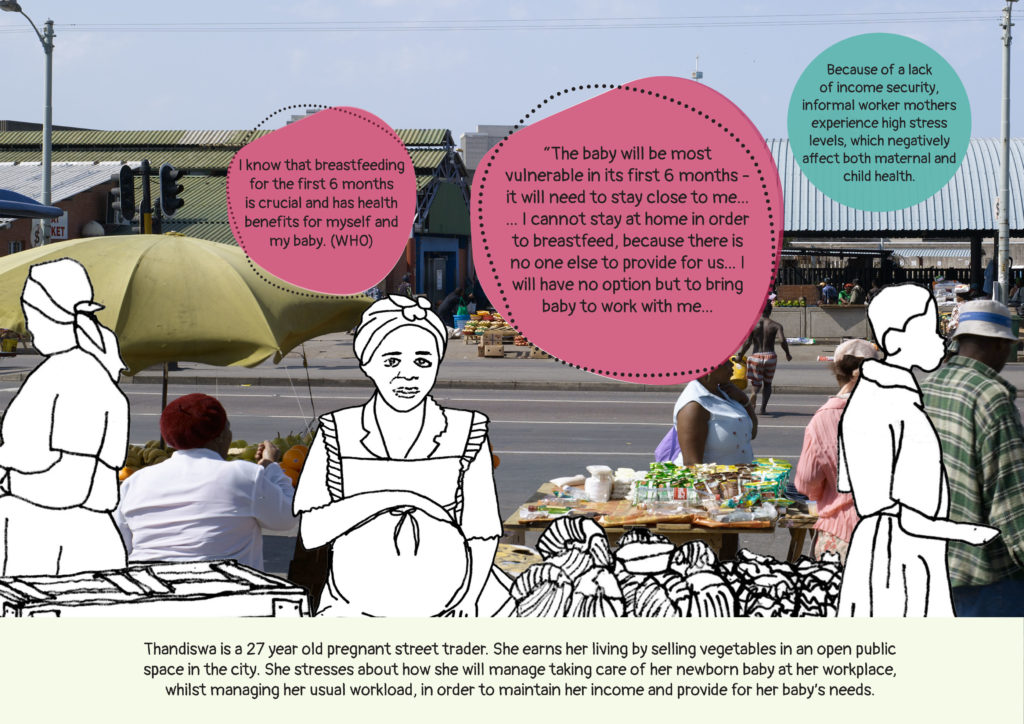

74% of informal workers (or traders) in Sub-Saharan Africa are women (WIEGO). Pregnant women are among the most vulnerable of these, facing socio-economic and physical obstacles to their maternal health throughout their pregnancies. After giving birth, they often have to choose between earning an income to financially support themselves and their dependents (including their newborn babies), and staying at home to breastfeed and bond with their babies.

At times, mothers are forced to bring their children to work because there is no one to look after them. In these cases, babies often sleep under trader tables. The dangers present on the street for newborn babies are obvious: noise, moving people, hazardous surrounding activities, and the inadequate provision of workplace infrastructure and basic services like clean and safe public toilets, shelter and furniture. Earlier this year, AeT observed that some women who brought their new-borns to work used crates – used to transport goods to and from their trading sites in the morning and afternoon – as a cot for their babies during the day. This local ingenuity and innovative use of technology prompted the idea of Umzanyana, drawing lessons from the Finnish “baby box” programme initiated from the 1930s.

The innovation: Umzanyana

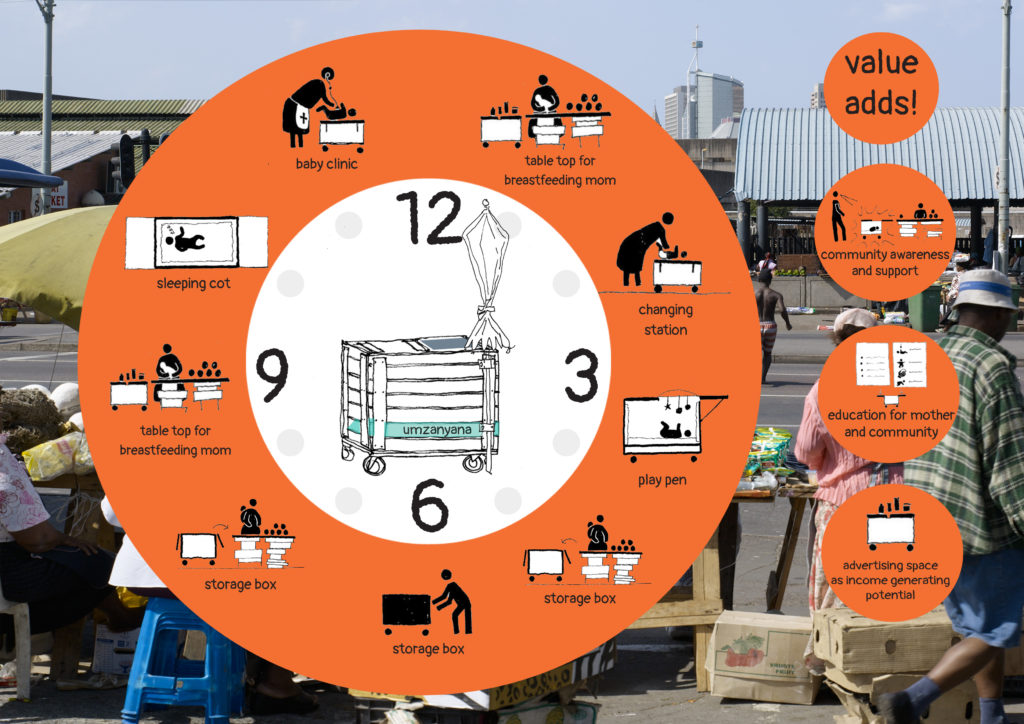

Directly translated from isiZulu, “umzanyana” means ‘umbilical cord’: an instrument of connection that allows the mother to give the baby what it needs. As an extension, it also refers to a close family member who acts as a wet nurse or baby sitter, who helps the mother take care of her newborn child. The concept re-purposes a vacant storage box during trading hours, allowing the urban community and the street itself to be a “helping hand” to the new mother during the day while she works.

The Umzanyana is a multifunctional wooden storage box, which is transformed into a temporary baby nursery. It would continue to function as a storage unit for the informal worker mother’s goods at night, and be used as a curbside nursery throughout the day (when it is usually unused). Essentially, the intervention would be a locally produced kit-of-parts, including components such as a soft sponge to line the inside of the box and act as a mattress, sheets for the baby to sleep on, a play mobile to stimulate the growing baby, and a form of protection from the elements. This kit would be issued to the mother over a 6-month period by a community health worker, who would also act as a roving nurse, visiting the mothers with babies at their worksites.

Technology among the working poor

The simplicity of this proposal, and many like it, makes it easy to ignore and difficult to mobilise funding. However, seemingly simple technological solutions like this may be more important than we initially perceive for the transformation of the ways in which we practice design and innovate with technology. The conversation about what technological innovation looks like in the informal economy for the working poor, and how we can learn from this, finds specific application in the Umzanyana.

According to Martha Chen’s collaborative research (“Technology at the Base of the Pyramid: Insights from Ahmedabad (India), Durban (South Africa) and Lima (Peru)”), the considerations guiding how technology is used among the working poor include limited resources, the risk of tools being stolen or confiscated, portability, storability and a lack of basic infrastructural services. The unfamiliarity of the challenges that informal workers navigate often makes the ingenuity of their technological innovations difficult to recognise for those who are not in their environment. However, the systemic, interconnected challenges facing the world today might require logics more like those of the informal economy than the logic of formal capital. Challenges like climate change, rapid urbanisation, growing inequality, and food security are complex and have been caused by the same logic we are using to innovate their solutions. The resilience and ingenuity of communities within hostile environments may well contain more fruitful ways of thinking than the ones we are familiar with.

Learning to read alternative innovations

The technologies mentioned in “Technology and the Future of Work” by Erik Lonne are often “about purposing and repurposing”. In the case of Umzanyana, it entails the repurposing of a box on wheels – an object used to support the temporary and mobile work environment of an informal worker – to create a safe micro-climate in the dynamic, harsh environment of the street. It repurposes an object that facilitates mobility, enabling it to facilitate stability. This suggests fresh, exciting ways of thinking about imminent challenges like migrant labour, homelessness and urbanisation.

Technology or tools also often function as ‘signs’ on the street: a means of communicating various messages to customers, co-workers and authorities. The low tables of traders with stock appealing to children, uniforms as a sign of legality to authorities, and water-carrying trollies that are used because they camouflage with surroundings and don’t draw attention to themselves, all communicate messages that facilitate or avoid certain transactions. In the case of Umzanyana, the message of the presence of the baby is communicated by the branded box. This message would serve to alert and include the surrounding community in the life of the baby. The box would form part of a holistic program, which would incorporate the production of the baby boxes by a local carpenter, the sewing of various components by local seamstresses, soft resources such as community health workers, and a general sense of community awareness of the baby to better support the mother and newborn.

As is characteristic of these interventions, the complexity of issues it engages with are not immediately apparent. Various narratives converge in this multi-purpose wooden box: narratives about mothers and the workplace, insecure livelihoods and family responsibilities, children and the city, technological innovation for working poor, urban communities and local economies, and mobility and security. Therefore, there are many ways to tell the story of Umzanyana. This is how we told it to Open IDEO. Unfortunately we were unsuccessful in the Open IDEO challenge and are still looking for funding to develop and prototype Umzanyana, both as a product and as a broader system that can significantly benefit mothers in the informal economy and their newborns.

We hope that as we and others learn to recognise innovation and local logic which we are unaccustomed with, we will open ourselves up to more simple solutions that can challenge current inefficient, unequal and unequitable systems more effectively.