Patrick Ndlovu & Tasmi Quazi

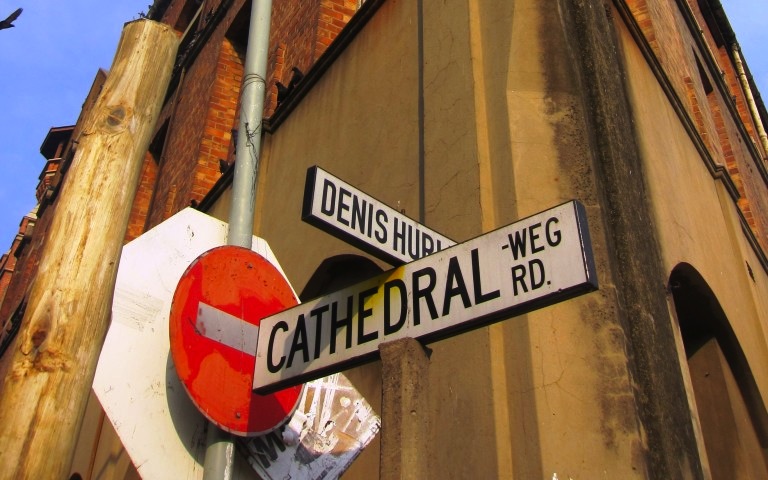

AeT’s role within the development of the Dennis Hurley Centre linked to the historic Emmanuel Cathedral – situated at the heart of Durban’s inner city – is to ensure the inclusion of informal workers in the precinct throughout the process. AeT’s primary role has been to facilitate better engagement between key role-players and informal workers in particular.

Some of the other role-players include the private developer (Emmanuel Cathedral), the contractors (Siya Zama), mini-bus taxi operators, local residents, formal businesses and City officials. After engagement with the key role-players, AeT facilitated the identification of alternative trading sites for 30 informal workers, and a holding area and ranking facility for nearly 50 minibus-taxis (including the relocation of taxi-shelters for commuters) affected by the construction phase.

The standard procedure during most construction phases of building projects results in the permanent displacement of informal workers (including taxi operators), or, where it subjects the remaining informal workers to unsafe working conditions. This project however has been commended for its proactive efforts to minimise the adverse impacts on informal workers in the following ways:

Retaining income-earning opportunities during the construction phase:

Bhekisile Thwala who has been trading in the precinct for 21 years, commented that although the pedestrian flow has been disrupted, she is grateful for the opportunity to continue working during the construction phase. She elaborates:

“Other areas, like the time the flyovers in Warwick Junction were being built around 2009, they didn’t allow informal traders to work outside the construction area. They just started the construction and didn’t care where the informal traders went. Also, when they wanted to break down the Early Morning Market and build a mall, they were going to do the same thing – which is why my friend who is a chicken seller in the market, protested against the mall. But in this project, we were informed in advance and accommodated. Even our complaints are addressed immediately like the dust and poor lighting levels. It shows that traders need to be consulted before and during building processes…”

Ensuring work-place security once construction is complete:

Similarly, Boy Ndlovu, a fresh produce trader working in the precinct for nearly 30 years, says that although the temporary hoarding arrangement has brought challenges to their working environment, he is grateful for the transparent process and feels assured that they will have access to their work-place once the construction is complete. He explains:

“Most projects, once they are upgraded, do not allow street traders to come back to work. This approach by the Dennis Hurley Centre should be practiced everywhere where traders are included from the planning stages and informed about how the development will affect their work. Usually City officials only come to talk to us when they are issuing fines, instead of talking to us when these kind of projects are being built…”

Investing in effective social facilitation services:

Aside from facilitating meaningful engagement with informal workers, AeT’s Senior Project Officer assigned as the Community Liaison Officer in this project, reflects on some of the unexpected tasks he has had to mediate:

“When the local civil construction industry was on strike, a unionist group intimidated the builders in the project to join the strike. I managed to convince the leadership of the union to not interfere with the builders who were technically not even a part of their sectors’ struggle…

…Taxi operators are notorious for being territorial and aggressive; but after a lot of negotiation between the developer and various taxi operators, over time, we managed to come to an agreement regarding their temporary relocation. I even got involved at the level of appealing for the traffic fines that were unjustly issued to specific taxi operators to be revoked – aggravated by the lack of effective communication between the Metro Police and a City department.

…There was also a request from the Ward Councillor to incorporate locals as labourers in the project. Subsequently through negotiations, the contractors provided 6 positions and the tasks range from providing assistance in first aid, building and cleaning services. Considering the small scale of the development, this is a good outcome.”

For AeT, this project has highlighted the value of incorporating social facilitation processes within development projects. This enables hands-on and continual engagement with key role players, especially with informal workers, so that issues can be raised and addressed immediately. This also allows the development team to learn from its mistakes and readjust the process for everyone’s benefit.

It however begins with the developers’ and contractors’ willingness to support the inclusion of informal workers by investing in effective social facilitation processes. In the case of the Dennis Hurley Centre, the developers have depended on AeT’s established street credibility with informal workers which has contributed towards the positive outcomes that this project is achieving, as a model for inclusive development.