Victoria Okoye

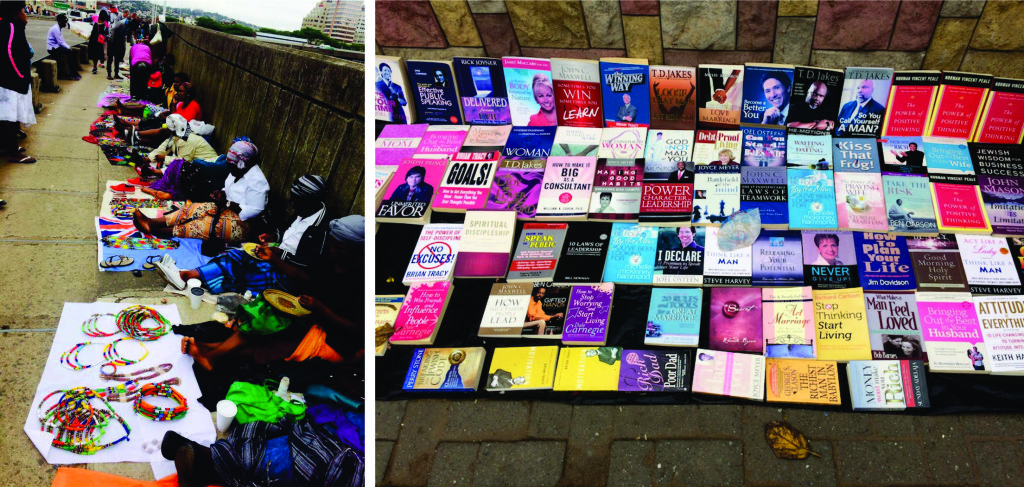

Every market has its own particular history, layout, social and economic dynamics, but in each and every market, vendors’ commercial dynamism creates a rich sense of place. For example, the Friday Bead Market at Warwick Junction is when and where the sidewalks of Russell Street overpass come to life. From early morning, bead makers sit along the sidewalk, their vividly colored necklaces, bracelets, headbands, belts and earrings arranged onto cloth sheets spread across the pavement. Countries away but in the same manner, street vendors along Derby Street at Accra’s Makola Market set up their sales on the sidewalk, each propping up neatly polished shoes, belts, purses and secondhand books onto thin sheets. In two very different cities, vendors temporarily transform sidewalks pavements into multifunctional spaces for market trade.

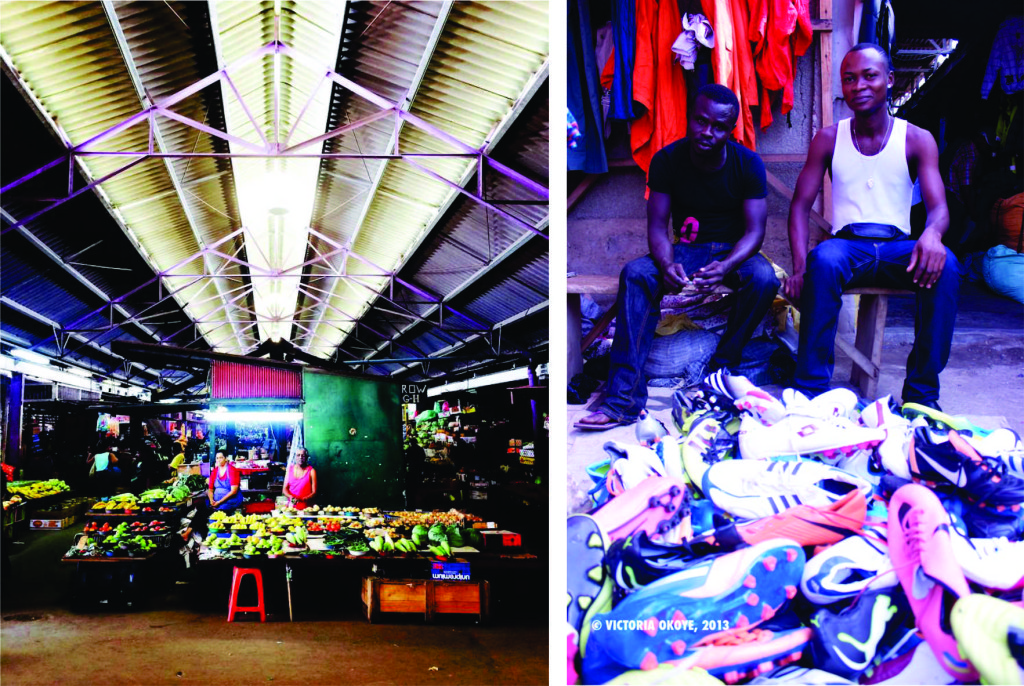

Other similarities exist. Like department stores, markets possess their own organization, sometimes planned by city authorities, sometimes developed through the agglomeration of vendors’ own activities. Vendors strike a delicate balance between commercial cooperation and competition, and the result is a locally contextualized spatial organization. Markets of Warwick, the nine markets located at Warwick Junction where 6000 vendors trade daily, provides an impressive example of precise product segmentation: Some of Warwick’s markets are incredibly specialized, such as the Herb Market (for herbal medicine) or the Impepho and Lime Market (for these two traditional products). In Early Morning Market, more variety exists; fruits and vegetables dominate there, but one can buy flowers and spices as well.

Kantamanto Market, an expansive secondhand market in Accra’s central business district, similarly has product-specialized retail sections where vendors trade in men’s clothes, women’s clothes, children’s clothes, music, shoes, and more, although the levels of organization are less strict. Similarly in Kumasi’s Central Market, with an estimated 15,000-20,000 traders, traders divide themselves by types of goods sold, by retail and wholesale trade, and even along ethnic lines, such as the Fante Market where Fante women dominate in the sales of smoked fish (Clark, 1994: 449).

These informal markets are generally collocated with transport hubs and exist as important nodes for global-local trade and provide key accessibility to everyday goods and services, making them important central business areas in the city. Given these characteristics, the growth of these major markets is often inevitable – and as the market increases in size, it expands spatially, and when unplanned, through a commercial transformation into adjacent sidewalks, streets and buildings. The commercial changeover from residential into commercial buildings and other related market uses is a common theme in areas near market spaces, which I first discovered researching Kaneshie Market in Accra.

In the 1970s, the Kaneshie Market was constructed as a multistory “modern market” in a low-density residential area. With time, the seed of commercial activity planted at the marketplace spread outward: Small-scale vendors appropriated sidewalk space, smaller businesses retrofitted nearby homes into commercial retail, and banks and financial services companies entered the scene to be close to their market customers. The result has been the evolution from a commercial market in the middle of a residential neighborhood into a full-out mixed-use and commercial zone. In Durban, Dr. Groonam Street (formerly Prince Edward Street), where two-story residential homes have been converted into semi-commercial, semi-storage spaces reminded me of the same phenomenon I saw at Kaneshie; of course, the specific types of commerce and products sold are driven by local dynamics in both spaces.

The construction of Kaneshie as a “modern market” also brings to the fore the continued focus of city governments on these developments across the continent. Authorities’ imaginations of African urban futures often involve public-private partnerships and large-scale, multistory market redevelopment projects (tagged “modern markets”), with centrally located commerce and sidewalks stripped of vendors. This vision challenges the existence and local dynamics of these informal markets, which are grounded in traditional culture. In 2015 in Kumasi, thousands of market vendors and street traders were displaced when existing markets were demolished to make way for new market construction. Earlier this year in Lagos, Oshodi Market traders were displaced for government redevelopment plans. Similar plans are in place for a number of markets in Accra. Warwick has faced this challenge, too; first in 2009, when the eThekwini Municipality proposed plans to replace the Early Morning Market with a shopping mall and minibus taxi rank. Although those plans were shelved, a new plan has been put forward, this time for the Berea Station area.

The dynamism of market culture is in its local culture and personal connections – even as trade evolves over generations, the markets’ vendors are what make it tick. Planning for the future of markets must involve the visions of all stakeholders, most especially these informal traders themselves, who bring their own informal expertise in designing, planning and organizing to maximize their productivity. For everyday customers, it’s the experience of their personal Friday Bead Market in their own city – with its local vendors, local products, and local connections – that make the retail experience a vibrant one.

Victoria Okoye is Urban Advocacy Specialist with Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO).

Additional References

Clark, G. (1994) Onions Are My Husband: Survival and Accumulation by West African Market Women. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press.

Mörtenböck, P.; Mooshammer, H. (eds.) (2015) Informal Market Worlds – Atlas: The Architecture of Economic Pressure. Rotterdam, NAI010 Publishers.

Rosenberg, L.; Vahed, G.; Haassim, A.; Moodley, S.; Singh, K. (2013) The Making of Place: The Warwick Junction Precinct: 1870s – 1980s. Durban, Durban Institute of Technology.