Tasmi Quazi

“Durban had been wrong to try to close down the Warwick Junction market and move traders into a new mall. It stopped listening to its own people before international input in the run-up to the 2010 World Cup (…) The 2010 World Cup in a lot of ways damaged our city… and one of these areas was Warwick Junction (…) It was going well until we started thinking international and not listening to local input. We need to hear their voices and bring them back to the table…”

These bold and apologetic sentiments offered by the Head of eThekwini Municipality’s City Architects unit, Jonathan Edkins, was one of the unforeseen yet significant outcomes of the prestigious Union of International Architects (UIA) Congress 2014 during the session titled “Global debates on access to the city: voices of Warwick”. The public apology appeared on the first page of the Mercury newspaper titled: “World Cup ‘damaged City’: The Warwick Avenue Mistake” on 5 August 2014.

Along with Jonathan Edkins, Asiye eTafuleni’s (AeT) Senior Project Officer, Patrick Ndlovu, and two informal workers from Warwick Junction were invited as panelists at the UIA 2014 debate session. The informal workers spoke emotively about the lack of supportive infrastructure and basic services, and how traders have been harassed by Metro Police, particularly in relation to the devastating impact of confiscations and during the 2010 World Cup. However, their grievances included suggestions for architects.

For instance, Zodwa MaDlamini Khumalo, a traditional healer who has been operating out of Warwick Junction for over 20 years, implored delegates that instead of favouring shopping malls which will ‘wipe out’ informal trade, they should help design better marketplaces for informal traders. A third-generation trader, Money Govender, said their market needed to be upgraded, and provided with amenities like cold rooms which are necessary to store their fresh produce.

At the UIA 2014 debate session, AeT’s Patrick Ndlovu said that when South Africa won the bid to host the 2010 World Cup, he knew the informal traders would be targeted yet again. This is what motivated him to resign as a City official and work for AeT in order to actively support informal workers’ livelihoods. He assuredly advised that,

“It is very important as architects and designers to understand the way the traders operate. We really want a design to make the place better (…) You will never go wrong if you interview the people there before you design and get their input.

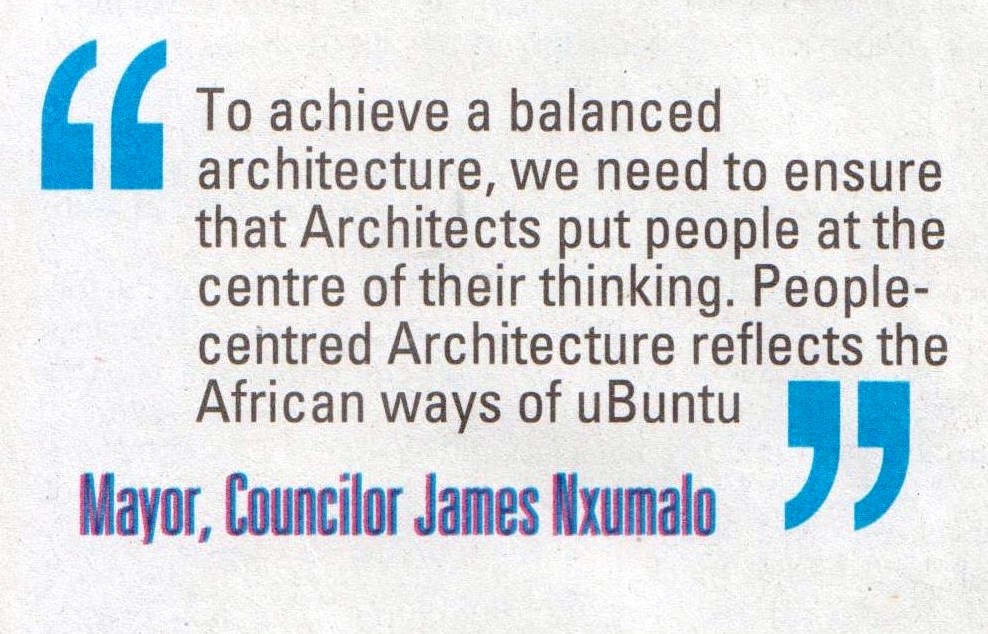

The significant statement by Jonathan Edkins was matched by political sentiment at the UIA 2014 opening ceremony, where the Mayor of eThekwini Municipality made this compelling declaration:

The Mayor’s reference to “Ubuntu” was later challenged by public representatives who wrote to the Mercury newspaper (19 August 2014, Page 7 in an opinion piece titled “City pays Ubuntu lip service”) saying, “We need to ask the Mayor whether he believes that what happened regarding the Warwick Triangle fits the definition of Ubuntu?” To drive the point of the central role of local government, they amended the Mayor’s statement to the following: “To achieve a balanced society, we need to ensure the municipality put people at the centre of their thinking. People-centred governance reflects the African way of Ubuntu”

Notwithstanding the significance of these high level apologies and sentiments, we believe that these need to not only be transmitted to, but also redress, the people affected by the legacy of these strategic decisions. As Brij Maharaj captured in a subsequent press article:

“According to the Global Charter Agenda for Human Rights in the City, all citizens have the right to: ‘a transparent and accountable city; participate in the decision-making processes of local public policies; and question local authorities regarding their public policies’. Assessing the Warwick market destruction and mall development against such international best practice criteria, reveals that the city has failed dismally.

The fatally-flawed planning fiasco in Warwick Avenue was driven by a top-down process which apparently favoured private sector interests. There were no transparent, competitive public tenders for the development of a mall on the market site.

There was no disagreement about the upgrading of services and infrastructure in the Warwick area. There was opposition to forced removal and relocation, evocative of the apartheid era, and the outcome will always be the same – the banishment of poor, black people to even greater levels of impoverishment.”

(To read more on Brij Maharaj’s article which appeared on page 7 of the Mercury newspaper, titled “Warwick Mall debacle reflects a shameful period”, click here.)

The apology and the subsequent debates represent a welcome turning point, which hopefully leads to a process of redress and new trajectories for people-centred development.