Sarah Heneck

With the world’s ever-expanding urban population and the need to focus on environmentally friendly modes of transport in order to decrease carbon emissions, non-motorized transport (NMT) has become a major focus for city planners. Those who use cycling and walking as their means of commuting to and from work are generally at the forefront of NMT plans. It is safe to say that when NMT is mentioned, one’s first thought is likely to be the green cycle lanes that have been painted on many roads in urban areas. Cycle lanes and walking routes are certainly an important aspect in the sustainability journey, but they do not tell the full story of NMT requirements in African cities.

There are hundreds of people in Warwick Junction and the Durban CBD who require NMT routes for activities vastly different from cycling and walking. As will be explained below, these people do not use these routes to get to and from work but rather to do their work.

Barrow operators loading their trolleys.

Barrow operators resting.

A barrow operator moving a traders goods to overnight storage.

Photo’s: Gerald Botha by permission Asiye eTafuleni

Barrow operators, water-carriers and informal recyclers are the main jobs in the city that are conducted on foot, with the use of only human strength and non-motorised equipment. This work is undertaken in the centre of Durban, on some of its busiest roads, and there is very little provision currently in place for these workers to safely transport goods from one place to another. These NMT operators offer essential services; barrow operators use metal barrows to transport produce (up to 600 kilograms of it at a time depending on distance of trips and terrain) to and from trading stalls in the markets of Warwick Junction and storage spaces; water-carriers, as the name suggests, transport water for the taxi’s and traders who don’t have immediate access to a water source, and informal recyclers collect (sometimes using trolleys) cardboard, plastic, glass and metal from all over the city and store it until it is collected by middle agents who then sell it on to recycling companies. These workers are forced to share the road with speeding vehicles because either there are no pavements, or the pavements are full of potholes, poles and rings intended for trees. There are also very few scoops which makes it near to impossible to hoist heavy equipment on and off the pavements.

Uneven surfaces within the markets. Photo: Gerald Botha by permission Asiye eTafuleni

Rings in the pavement intended for trees. Photo: Angie Buckland by permission Asiye eTafuleni

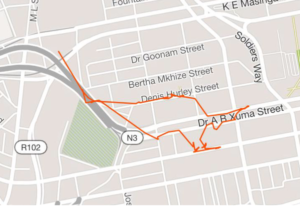

In order to gain a little bit more of an understanding of the working life of a barrow operator we accompanied Vuyani on one of his trips. We followed him from the Early Morning Market in Warwick Junction on a 3.5 kilometer round-trip during which he dropped off produce at 5 different traders situated in central Durban. Even though he was pulling approximately 250 kilograms of produce, we struggled to keep up with him! Numerous times on the trip I was terrified for his life as cars and trucks sped past him and he had no choice but to stay on the road because the pavements are not conducive to pushing a barrow laden with hundreds of kilograms of vegetables.

Vuyani had an experience which highlights the high level of risk of this job – in February 2018 Vuyani was hit by a truck while pushing his barrow up David Webster St [former Leopold St] and dragged for 100 meters down the road. Luckily, the only lasting effects of his accident is a slight limp and metal pins in his leg, but the outcome could have been far worse. He had to take 10 months off work and is still waiting to be paid out by the Road Accident Fund. Along with the dangers of the job, the barrow-operators are also subjected to harassment and confiscation of their goods by law enforcement.

At the first stop on our trip, on what we found out was already his second trip of the day (at 8.30 in the morning), he dropped off a large bag of green peppers and was paid R15 (around $1 USD) in return. The other 4 traders for whom he dropped produce off didn’t give him money – he would need to wait till the end of the day for these payments because the traders first need to sell the produce before they are able to pay him. Trust is an invaluable commodity in the informal economy; in addition to Vuyani’s trust in his customers to pay him back, much of Vuyani’s load had been taken on credit from the suppliers who would only get their money once Vuyani returned with cash from his customers. Furthermore, I was very surprised when Vuyani left his barrow on the side of a very busy road while he ran to a public lavatory. I was assured that nobody would touch his goods as that is “street law.” We arrived back at the Early Morning Market an hour and 20 minutes after we had left and Vuyani immediately began to reload his now empty barrow, as he would 3 or 4 more times that day. The strength required for this line of work is hard to fathom, and despite how hard he is working everyday, Vuyani is likely to be considered unemployed.

Vuyani, unable to utilize or access sidewalks, faces oncoming traffic. Photo: Sarah Heneck

Vuyani’s heavy load. Photo: Sarah Heneck

Workers like Vuyani are central to the informal economy and planners dealing with NMT need to broaden their focus to take into consideration the diverse range of street users in the city. An inclusive city should be aware of all the cogs which keep it functional.

[Feature photo: Barrow operators from Warwick Junction. Photo credit: Angie Buckland by permission Asiye eTafuleni]